NEW GALLERY PREVIEW

Exhibition Dates: December 18, 2025 – February 13, 2026

Viewings by appointment

2447 Main Street

Santa Monica, CA 90405

Trotta-Bono Contemporary presents our new private exhibition and advisory space within the iconic Frank Gehry-designed Edgemar complex. This intimate, curated environment marks the next step in our mission – to create deeper, more intentional ways of experiencing and collecting contemporary art.

Since its founding, Trotta-Bono Contemporary has championed artists whose practices expand and redefine the landscape of 20th and 21st century art. Central to our program is a sustained commitment to contemporary Native American art – a field experiencing a transformative and long-overdue rise across institutions, collectors and the global market.

Our program continues to spotlight this powerful ascent – an area where we are honored to be at the forefront – while presenting a broader range of artists shaping today's cultural discourse. The space is designed for focused exhibitions, artist projects and elevated client engagement. It offers a setting where artworks can be experienced with clarity, context and depth.

Through rotating presentations and client advisory, this new space will serve as a hub for scholarship, discovery and meaningful collector relationships.

THE ARTWORK

RICHARD GLAZER DANAY

Richard Glazer Danay brings his irreverent wit and Pop Art sensibility to bear in this bold reworking of an American icon. At the center, a green, glittering silhouette of Mickey Mouse raises two pistols in a cartoonish Western stance, set against a dark ground animated by sketched cats that drift like background noise or afterimages. Along the left, right, and bottom edges, thick bands of the same green glitter frame the scene, each topped with a marching procession of bison—part parade, part border, part provocation.

A longtime figure aligned with the Pop Art movement, Glazer Danay was drawn to mass media imagery, cartoons, and consumer symbols, using them to expose the absurdity and violence embedded in American mythology. Here, Mickey’s playful familiarity collides with guns, frontier posturing, and Indigenous symbolism, collapsing entertainment, power, and history into a single stage. The work exemplifies Glazer Danay’s personality-driven practice—satirical, mischievous, and pointed—where humor becomes a sharp tool for critique and Pop iconography is repurposed to question who controls the narrative and why.

FRITZ SCHOLDER

In this monumental circular painting, Fritz Scholder reclaims the visual language of the Native American shield and repositions it within the scale and urgency of contemporary art. Set against a stark, gestural white ground, a massive buffalo skull occupies the center—an image historically painted onto shields as a symbol of protection, sustenance, and spiritual power. Scholder amplifies this form to an uncommon scale, pushing the shield motif into the realm of Pop-inflected spectacle and confrontation.

A violent splatter of red paint cuts diagonally across the surface, bleeding into the skull itself and disrupting any sense of reverence or distance. The gesture injects immediacy and unease, where tradition collides with modernism, ritual with rupture. Widely regarded as one of the most important figures in postwar American art and the pivotal force of the American Indian Art Movement, Scholder brought Native experience into the global contemporary art conversation. This work stands among his most compelling shield paintings—an homage to Indigenous visual systems and a stark reckoning with the bloodshed and unresolved histories bound to them.

CARA ROMERO

Continuing in the theme of Indigenous Futurism, I tell stories that I want to breathe into existence – futures where our heirloom corn continues to flourish and our ancestral knowledge serves as the foundation for human and planetary wellbeing. In this work, I reimagine the timeless figure of Coyote (and she’s in female form) in a futuristic setting. Coyote Girl emerges from her spaceship, inviting us to wonder what adventures await in this playful fusion of ancestral story knowledge and speculative possibility. Our fabled trickster, Coyote, teaches lessons of humanity: how to be a good person, how to learn from mistakes, and how to maintain a sense of humor and adventure even in uncertain times.

The photograph features Peshawn Bread (Comanche/Kiowa) as our heroine Coyote Girl, captured on Santa Fe's Southside near the spaceship sculpture. My team and I created the otherworldly atmosphere using colored gels over strobe lights – you can see their reflections in her glasses – fog effects, and sparklers attached to her toy gun. I added the aurora borealis and stars through photo illustration, referencing the rare Northern Lights that were visible here in Santa Fe last winter.

While it is hard to explain cross-culturally the importance of our community stories and languages, they are integral parts of our ecosystems. Language and stories from the landscape are not separate from environmental science – they provide an important confluence to the unknowable value of Indigenous science, philosophy, and spirituality. I hope that today and well into the future, we continue to value the stories of our creations and mythos.

–Cara Romero

RICK BARTOW

In Big Wolf Dancer, Rick Bartow presents a rare and deeply personal self-portrait in which he appears bound to the wolf in a moment of transformation and communication. While Bartow frequently depicted dogs and coyotes, this is one of the few works in which he identifies the animal specifically as wolf—a figure tied to ceremony, endurance, and spiritual lineage. The pose suggests exchange rather than control, positioning the wolf as both guide and witness.

Bartow often referenced sweat lodge, ceremony, and pow-wow through words such as chant, song, and dance, and this work operates in that register. His red nose, a recurring self-identifier, reflects his long struggle with alcoholism and his hard-won sobriety after 1979, a condition he described as ongoing rather than resolved. Fragmented text drifts through the composition, including veiled literary and personal references—one alluding to Shakespeare’s Macbeth, another to a close friend, collaborator, and source of support in Bartow’s recovery whose family crest is the wolf. Grounded in Wiyot cultural history, where “Wolf’s House” names an important village and ceremonial site, Big Wolf Dancer frames transformation as a lifelong practice of listening, carrying, and moving in step with what endures.

TONY ABEYTA

In Animal Dance, Tony Abeyta channels raw movement and ritual energy through a stark palette of black and red. Masked figures with ovoid eyes overlap and collide across the surface, their fractured forms recalling both ceremonial presence and the dynamism of modernist abstraction. The composition carries a Picasso-like intensity, where bodies and symbols dissolve into rhythm rather than narrative.

The work is encased in a hand-hammered copper frame created by the artist himself, its indented, oxidized surface echoing the imagery within. Copper—long associated with energy, protection, and transformation—extends the painting beyond the canvas, reinforcing the sense of dance as both physical and spiritual act. Together, painting and frame form a unified object, asserting Abeyta’s synthesis of Diné ceremonial consciousness and contemporary abstraction.

In Deer with Magpie, Tony Abeyta composes a fluid, atmospheric field of floating imagery where animals, symbols, and abstraction move in rhythmic dialogue. Deer, antlers, and a magpie drift through overlapping planes of deep magenta, red, green, and earth tones, suggesting cycles of migration, shifting weather, and the constant motion of the natural world. Forms emerge and dissolve, echoing the way landscape, animals, and spirit are understood as interconnected rather than fixed.

A horned shield appears in the lower corner, grounding the composition in protection, ceremony, and ancestral memory. As in much of Abeyta’s work, reverence and energy coexist—nature is not observed from a distance but experienced as a living system in motion. Through layered paint, gesture, and symbolism, Deer with Magpie reflects a Diné worldview in which balance is found through movement, transition, and the enduring presence of the land and its beings.

In Celebration from the Underworld, Tony Abeyta creates one of the most ambitious and profound works of his career—a monumental vision of Diné cosmology rendered with extraordinary confidence, scale, and painterly force. Stretching nearly eleven feet wide, the canvas unfolds as a charged field of figures, symbols, and mythic references, where celebration and ceremony emerge from beneath the surface of the visible world. The “underworld” here is not a place of darkness, but one of origin, transformation, and renewal.

Abeyta layers dense impasto, sweeping gestures, and luminous color to build a composition that vibrates with movement and energy. Human and spirit forms, ritual iconography, and abstracted elements collide and cohere, creating a visual rhythm that mirrors Navajo ceremonial cycles. Levity and reverence exist simultaneously—joy, humor, and gravity intertwined—reflecting a worldview in which balance is achieved through continual motion and exchange.

Widely regarded as one of the leading Indigenous painters of his generation, Abeyta bridges ancestral knowledge and contemporary abstraction with rare authority. Celebration from the Underworld stands as a tour de force: a painting that insists on scale not for spectacle alone, but to hold the weight of mythology, memory, and living cultural continuity.

EMMI WHITEHORSE

Emmi Whitehorse is a foundational figure in contemporary Indigenous abstraction, widely recognized for expanding modernist painting through Diné philosophy and land-based ways of seeing. In recent years, her work has received major institutional recognition, including prominent retrospectives and acquisitions by leading museums, affirming her central place in American art history.

In #950, Whitehorse layers translucent fields of deep magenta and red with delicate lines and glyph-like marks that suggest land, movement, and memory rather than literal depiction. The composition invites a shifting way of seeing—forms feel both intimate and expansive—asserting abstraction as a site of Indigenous knowledge, presence, and continuity.

A leading voice in contemporary Indigenous abstraction, Emmi Whitehorse has gained renewed recognition through major museum exhibitions and national honors that underscore her lasting influence on modern painting. Her work bridges Diné philosophy and abstraction, offering a visual language rooted in land, memory, and perception.

In #1057, translucent fields of orange and yellow are layered with subtle markings and gestures that evoke atmosphere and horizon without direct representation. The painting encourages movement between close detail and vast space, affirming Whitehorse’s role in redefining abstraction as a powerful, Indigenous-centered mode of expression.

KENT MONKMAN

Study for nîtisân (My Sibling) is based on a Jules Breton painting and depicts four Indigenous siblings stealing a moment together during long hours of forced farm labour to secretly speak their language and harvest wild ginger—a medicine plant. Despite the buccolic serenity of the scene, the children are not out of harm’s way. Briefly reunited at a safe distance from the work camp buildings and the punitive gaze of their harsh schoolmasters, a young girl speaks softly in Cree to offer words of comfort to her homesick younger brother separated by a small creek. The painting reflects how the children’s work camps separated families and enforced strict gender binaries, but the children’s defiance in speaking Indigenous languages despite the risk of harsh punishment, and their practice of covertly harvesting medicinal plant knowledge, speaks to the resilience of Elders in preserving our ways of knowing.

— Kent Monkman

Many of our Elders and ancestors ran away from harm they experienced at the children’s work camps during the century that this ruthless assimilationist system was strictly enforced by government policy. Some of the children did not survive their journey home, which often involved travelling hundreds of miles by foot in unforgiving weather and rugged terrains. The tender-aged children in Study for The Going Home Star are depicted navigating their escape. The Going Home Star—kîwêtin acâhkos in Cree astronomy, known to some as Polaris, the North Star—stands still in the night sky, acting as a guide for travellers. Using traditional knowledge, the children plot their way home while the shadows of thunderbirds—their protectors—pass over them in the approaching dusk.

— Kent Monkman

Set against a Bierstadt-inspired mountain landscape, The Annunciation depicts Indigenous and Anglo men wrestling, playing music, and celebrating by the lake, all charged with Monkman’s sharp satire and humor. Floating above them is Monkman’s alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle – a Christ-like figure who both blesses and playfully challenges narratives of power and identity. A bare-chested, painted Scotsman draped below the waist humorously blurs cultural lines, recalling historic Rendezvous gatherings as sites of alliance and cultural negotiation. The painting reclaims a landscape often erased by Western expansion, repopulating it with Indigenous presence, queer resilience, and ironic wit.

DAN NAMINGHA

In this early abstract landscape, Dan Namingha translates the Southwestern terrain into a language of color, gesture, and form. A single, electric mesa line stretches across the upper third of the canvas, anchoring the composition while activating the surrounding fields of color. Earthy reds, ochres, and deep magenta collide with expressive brushstrokes, evoking land, sky, and movement without settling into literal description. Subtle cues at the top of the painting reveal a nocturnal setting, lending the work a quiet, atmospheric charge.

Created in 1983, the painting reflects a formative period in Namingha’s career, when abstraction became a means of expressing place, memory, and cultural continuity rather than depicting landscape directly. Rooted in Hopi sensibilities yet firmly engaged with modernist painting, the work captures the Southwest as lived experience – felt, remembered, and reimagined – asserting an Indigenous abstraction that is both timeless and unmistakably contemporary.

MARGARETE BAGSHAW

Margarete Bagshaw is known for an abstract style that draws from landscape through color, structure, and restraint rather than direct representation. In this pastel work, red, white, black, and orange tones are layered in shifting fields, creating a composition that feels both grounded and expansive. Subtle variations in mark and density suggest movement, horizon, atmosphere and figure while maintaining a quiet, disciplined surface.

The drawing is presented in a hand-carved wooden frame made by the artist’s husband who was a master woodworker, a detail that reflects the care and craft surrounding the work without overtaking it. Together, image and frame underscore Bagshaw’s measured approach to abstraction—one rooted in place, balance, and a deep engagement with material and form.

RICHARD GLAZER DANAY

In this vertically divided mixed-media work, Richard Glazer Danay stages a collision of devotion, spectacle and Pop absurdity. A central retablo anchors the composition, while the surrounding imagery fractures into two contrasting realms. Below, floating pink bison drift across a gray field in varied orientations – weightless, playful, and destabilized – culminating in a toy pink bison assemblage at the base.

Above, the palette darkens. Black, glitter-laden surfaces hold bison skulls suspended in multiple orientations, their reflective grit oscillating between reverence and critique. As in much of Glazer Danay’s practice, the work blends humor with unease, folding sacred reference into mass-produced iconography. The result is a restless tableau that questions how symbols migrate, lose gravity, and are remade – where devotion, commodity, and cultural memory occupy the same uneasy frame.

In this vertically oriented mixed-media work, Richard Glazer Danay layers disparate visual languages into a single, charged tableau. At the center sits a Hispanic retablo, anchoring the composition in devotional tradition, while the surrounding imagery fractures any sense of stability. In the lower register, a female figure rendered in Aboriginal-style dot patterns appears suspended in space, spear in hand, encircled by sharks – at once grounded, endangered, and defiant. She reaches upward, grasping an airplane that propels the eye into the upper fields of the work.

Black, silhouetted aircraft scatter across a blue sky, moving in conflicting directions. Above them, a dark, glitter-inflected grouping of dotted birds hover in the upper third, evoking flight, freedom and transcendence. As in much of Glazer Danay’s practice, Pop imagery, spiritual reference, and global symbolism collide with humor and unease. The work reads as both spectacle and critique – an irreverent, restless composition that reflects the artist’s engagement with power, movement, and the absurd choreography of the modern world.

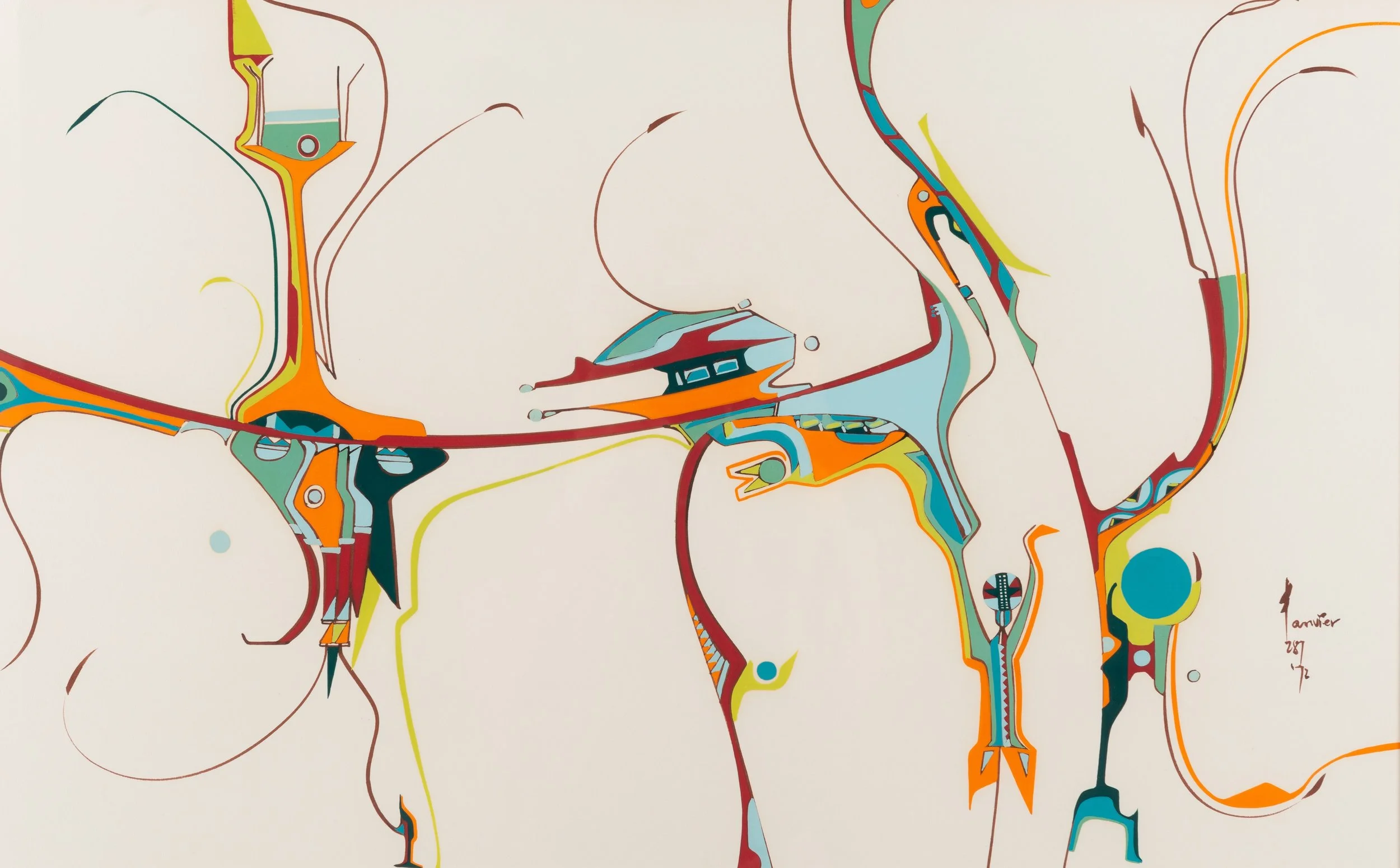

ALEX JANVIER

In The Caller, Alex Janvier distills movement, sound, and presence into a web of fluid line and restrained yet charged color. Spidery, meandering strokes pulse across the surface, where deep magentas and sky blues quietly clash with bursts of orange and grounding greens. The composition hovers between abstraction and representation: two central forms suggest animate bodies, their whiplashing extensions recalling bulrushes or buffalo tails, while serrated motifs echo ancestral adornments from Denesuline material culture. Scattered triangles, chevrons, lozenges, and geometric forms reference the visual languages shared across many Plains Nations, translated here into a contemporary, rhythmic syntax.

Created in 1972, The Caller marks a pivotal moment in Janvier’s career and in the history of contemporary Indigenous art. That same year, Janvier – alongside Jackson Beardy and Daphne Odjig – participated in the landmark exhibition Treaty Numbers: 23, 287, 1171: Three Indian Painters of the Prairies at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, the first exhibition devoted exclusively to contemporary First Nations artists in a Canadian public institution. In this work, Janvier asserts a visual language that is both modern and deeply rooted – one that calls across time, culture, and place, insisting on Indigenous presence within the evolving discourse of abstraction.

DAVID BRADLEY

In Kicking Bear, David Bradley adopts the visual language of Pop Art – most notably the serial repetition and high-key palette associated with Andy Warhol – to interrogate how Indigenous leaders have been flattened into historical icons. The Lakota chief Kicking Bear appears four times, each iteration rendered in shifting fields of pink, blue, green and yellow. Face and sky trade colors across the quadrants, destabilizing any single, authoritative image.

By repeating and recoloring a figure so often fixed in the historical imagination, Bradley exposes the ways Native identity has been reproduced, consumed and aestheticized. The work is at once playful and pointed: a critique of celebrity culture, historical reduction, and the mechanisms through which Indigenous figures are transformed into symbols rather than understood as complex individuals.

Hopi Maiden employs the same Pop-inflected strategy of repetition and color variation to examine the construction of Indigenous femininity. Four identical images of a Hopi woman – her hair styled in traditional squash blossom buns – appear across the surface. Each image rendered in alternating fields of pink, blue, green, and yellow. As with Kicking Bear, color shifts between figure and background deny any stable or singular reading.

Bradley’s use of serial imagery references both mass media and art history, while quietly critiquing the romanticized and ethnographic framing of Native women. The work resists the notion of the “timeless” or “authentic” maiden, replacing it with a dynamic, contemporary image shaped by visibility, reproduction, and cultural expectation.

GEORGE MORRISON

Created in 1957, this abstract composition exemplifies George Morrison’s distinctive approach to Abstract Expressionism through a restrained palette of black, white, and grey. Dense passages of mark-making, layered gesture, and shifting tonal contrasts generate a powerful sense of movement and depth. While non-representational, the work suggests horizon, land, and atmosphere—early expressions of spatial concerns that would remain central to Morrison’s practice.

Long underrecognized within dominant narratives of postwar abstraction, Morrison’s work has experienced an extraordinary resurgence of institutional and critical attention in recent years. Major museum exhibitions and acquisitions have firmly repositioned him as a central figure in American Abstract Expressionism, culminating in a landmark solo retrospective at The Metropolitan Museum of Art earlier this year.

This grouping brings together seminal works by Betye Saar and her daughters, Alison Saar and Lezley Saar – three artists whose distinct practices are linked by a shared engagement with material, memory, and transformation. Created between 1980 and 2002, these works reflect a pivotal period when each artist was actively shaping the language of contemporary American art through assemblage, sculpture, and symbolic narrative. Seen together, they form a rare intergenerational dialogue in which lineage functions not as inheritance alone, but as continual reinvention.

Betye Saar is a foundational figure in postwar American art, widely recognized for pioneering assemblage as a means of cultural critique, spiritual inquiry, and feminist resistance. Drawing on found objects, folk traditions, and African diasporic symbolism, her work transforms everyday materials into charged, talismanic forms that confront racism, sexism, and historical erasure. By the 1980s and 1990s, her practice had become increasingly refined and mythic, exerting profound influence on subsequent generations.

Alison Saar extends this legacy through sculpture and drawing that center the human body as a site of labor, endurance, and resilience. Working in wood, bronze, and found materials, her figures bear the physical and emotional weight of history, addressing race, gender, and power with unflinching presence and scale. Lezley Saar expands the conversation inward, constructing psychological and theatrical worlds where identity is fluid, performative, and shaped by memory and imagination.

Originally shown through Jan Baum Gallery in Los Angeles – long a critical advocate for artists working across assemblage, feminism, and cultural critique – this grouping carries important historical resonance. Together, these works illuminate a continuum of influence and independence, revealing how ideas move across generations and how art can function simultaneously as inheritance, challenge, and renewal.

Betye Saar, Alison Saar, Lezley Saar

Selected Works, 1980–2002

Assemblage, sculpture, mixed media, works on paper

Originally acquired from Jan Baum Gallery, 1970

BETYE SAAR

Artist’s Statement:

My recent art works have been collages and assemblages incorporating vintage photographs of African-Americans. I selected this violin because of its rich character and color of the wood. My great uncle, Robert Keyes, had a restaurant called 'The Libya' on West 139th Street in Harlem, New York. The Libya was a large, two-story house and the ground floor was the restaurant. The 1914 photograph is of the restaurant's band as they posed in the garden with each musician holding his instrument. The women played the piano and sang. The band performed popular songs of the day, waltzes and maybe even a ragtime tune.

Betye Saar’s artwork has a vivifying quality and the underlying messages typically possess significant depth. ‘HooDoo’ references the varied spiritual practices, traditions and beliefs that were created by enslaved Africans in the United States from various traditional African spiritualities, religions and indigenous botanical knowledge. HooDoo #18 is a visually complex and rare artwork from this exciting series and period for the artist.

LEZLEY SAAR

Nature, technology, assemblage and the act of human intervention (the act of creation) are critical components to the working practice of the artist. The featured artwork represents a masterful combination of these elements. The intricate painting depicts a tree growing from the womb of a woman, suspended in mid fall. Books symbolize knowledge, wisdom, technology and perhaps hidden truths. The image, nestled within the cover of a leather-bound book, is caged behind the wooden spindles of a wall hanging - an iconic example of traditional Americana. The work, further accented by bits of nature (moss and acorns), shows an incredible attention to detail and artistic precision while overlapping thoughtful meaning.

The housing for this artwork is a physical yearbook from the class of 1938 at the University of Oregon at Eugene. The front and back covers feature a sea of white men (boys) frolicking in the water. Cut out from the center, the heart of the yearbook, is a piece of assemblage. In line with the practice of Lezley Saar and her lineage, the placed object is a painted mirror of a man and woman, in traditional white colonial gown attire, with dark skin. The mirror is abraded and cracked. The artist is portraying a rich commentary on society, race, knowledge and contradiction.