Exhibition Dates: August 9–30th, 2025 | Viewing Hours: Tuesday–Sunday, 12:00–5:00 PM

Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) Santa Fe | 906 S. St. Francis Dr., Santa Fe NM, 87505

The Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) Santa Fe presents Reservation for Irony: Native Wit and Contemporary Realities, an exhibition that explores the role of satire, humor, and visual wit in contemporary Native art. Curated by James Trotta-Bono, the show brings together work from a dynamic cross-generational group of Indigenous artists whose practices cut across media, movements, and tribal affiliations.

Collectively, these artists wield humor as a sovereign language – piercing through the fog of erasure, romanticism, and historical distortion that has long clouded Indigenous representation. Through painting, sculpture, photography, performance, and installation, these artists deploy irony not as mere provocation, but as a deeply rooted cultural strategy. Trickster figures, double meanings, visual puns, and biting wordplay animate the work, grounding it in centuries-old storytelling traditions where laughter is a way of teaching, healing, and thriving.

The works in Reservation for Irony confront the layered politics of otherness – how Indigenous people have been imagined, erased, exoticized, pitied, and legislated into silence. With satire as their scalpel, the artists cut through borders both literal and symbolic – immigration policy, Manifest Destiny, blood quantum and the myth of the “vanishing Indian.” They challenge cultural gatekeeping, spiritual appropriation, and the fantasy of “playing Indian”, while addressing the legacies of the systemic harm of boarding schools, coerced adoption, addiction, land theft, and forced relocation. Deeply interconnected themes overlap and collide – the sacredness and seizure of land, the fluidity between traditional and contemporary identity and the re-contextualization of trauma with sharp humor. From vinyl albums to Hollywood tropes, riot police to trickster figures, the works insist on contemplation. They invite viewers to sit in the discomfort where irony cuts deepest, where laughter and critique become inseparable acts of sovereignty.

Reservation for Irony is a celebration of the complexity, resilience and creative depth of Indigenous artists. These storytellers offer clarity without simplicity, memory without nostalgia, and resistance without bitterness.

To laugh here is not to look away, but to look deeper.

PRESS

View the virtual walkthrough of the exhibition with James Trotta-Bono.

THE ARTWORK

Untitled, 1985

Bob Haozous’ steel bear cutout playfully bridges tradition and performance, embodying strength with a whimsical, dancing presence. Its bold, heavy form is softened by harmonious curves and an open mouth that invites connection, while the bright red heart-shaped cutout reveals the vulnerability at the bear’s core. This sculpture celebrates the dynamic spirit of the bear as both protector and living being, blending Indigenous cultural reverence with joyful vitality and theatrical expression.

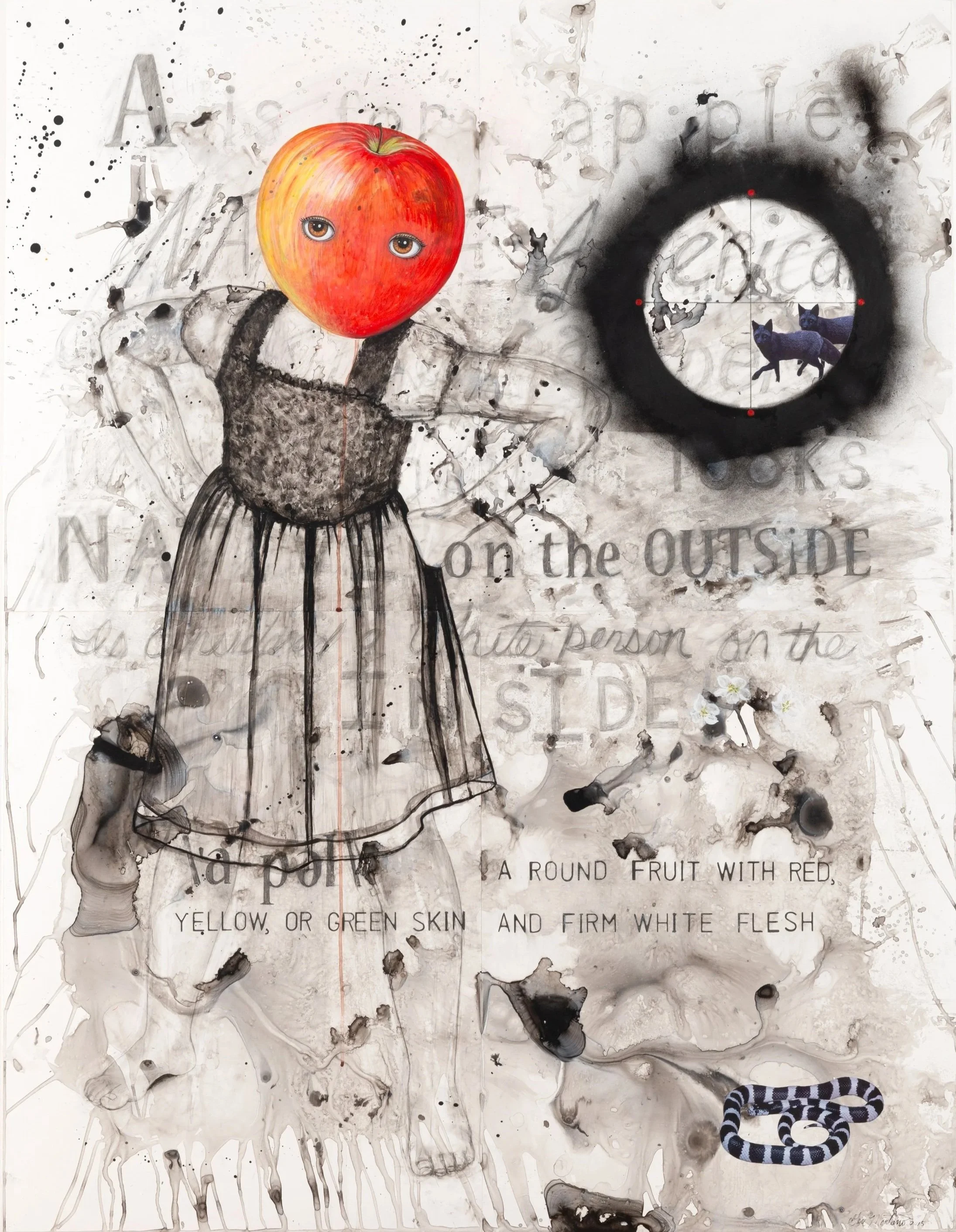

GERALYN MONTANO

Forbidden Fruit, 2016

In Forbidden Fruit, Geralyn Montano uses biting satire to explore the complexities of growing up distanced from her Indigenous roots. The faceless woman in a historical dress, her head replaced by a painted apple, reflects the slur often used to describe the urban Native experience – seen as “white on the inside.” Phrases like “A is for Apple” and “Native on the Outside” point to the psychological toll of assimilation and estrangement. Crosshairs scatter the surface, one over the word “American,” as two coyotes walk through them – a nod to survival, resistance, and trickster intelligence. A snake winds along the bottom like a warning – or a clue. With layered media and layered meaning, Montano reclaims the apple, turning a symbol of erasure into a badge of complicated truth.

HARRY FONSECA

Coyote in Front of Studio, circa 1980s

Harry Fonseca’s Coyote in Front of Studio satirizes the enduring “real Indian” stereotype through a playful reimagining of the cigar store Indian. Coyote, the trickster, stands on a wooden crate outside the artist’s Albuquerque studio, door marked 1035, wearing 1980s jeans and sneakers, mirrored sunglasses, and a glittering feather headdress. In his hands he holds a bag of marijuana and a fistful of joints, merging sacred symbolism with modern subversion. Fonseca’s lively brushwork, glitter, and reflective surfaces give the painting a vibrant, irreverent energy that draws the viewer in before revealing its deeper critique: the persistent commodification of Native identity, the humor and adaptability of the trickster, and the tension between cultural myth and lived reality.

DIEGO ROMERO

Der Esel Wagon, 2007

Diego Romero’s ceramic pot masterfully intertwines traditional Mimbres and Puebloan geometric motifs with contemporary comic and pop art influences. The checkered white and gold rim delicately contrasts with the central, comic-style depiction of Choco – a recurring Puebloan alter ego – and a white woman in a moment of passionate intimacy inside a car. Sweating and marked with exclamation points, their intertwined figures express raw sexuality, tension, and humor. Through this bold fusion, Romero challenges conventional perceptions of Indigenous art and identity, using humor and explicit storytelling to explore themes of cultural encounter, desire, and the complexities of human relationships.

TONY ABEYTA

Top Shelf / Garden de Luxe, 2025

I grew up in Gallup, New Mexico in the 1970s, during an era when alcoholism prevailed—with a profound and lasting impact on the Navajo/Diné communities. Gallup is a small city along Route 66, ringed by Native American reservations and split by the railroad. It served as a commercial hub and weekend gathering place—but also as the epicenter of a devastating epidemic of alcoholism within the Navajo/Diné community.

Locally, “GD” referred to Garden de luxe, a cheap Tokay wine produced by Joe G. Maloof & Gallup Sales Co., notoriously bottled from the dredges of low-end California wineries and shipped in on tanker trains. Along with its counterpart, Roma, it was potent, inexpensive, and consumed largely by street drinkers, those unwelcome in bars. The drink no longer exists—except as bad memories to those who witnessed its wrath.

In winter, those who froze to death after drinking were grimly nicknamed “Popsicles” and recorded by police as “203s.” The alleys, riverbeds, and foothills were littered with empty bottles. Even now, as the sun sets over Gallup, the hills still glitter with broken glass—silent monuments to decades of loss.

My childhood passed amid movie theaters, baseball games, sunburned foothills, and bike rides past makeshift camps. Alcohol seemed harmless—until it claimed friends, neighbors, and family.

This work is both remembrance and elegy. It reflects on Gallup’s grim moniker as “the drunk capital, USA,” yet also acknowledges resilience. When I visit the local flea market, the scent of burning sage still cuts through the air, offering ceremony, healing, and hope.

The painting is a prayer for those who never found recovery.

– Tony Abeyta

CANNUPA HANSKA LUGER

Untitled, circa 2017

CARA ROMERO

Fawn, 2025

Fawn Douglas (Las Vegas Paiute Tribe) stands with an omniscient look. We wonder how many of you are knowledgeable about the Las Vegas Paiute Tribe, or how their homelands in Las Vegas, Nevada, are some of the most sacred cultural landscapes to Nüwü or Southern Paiute people. The young city of Las Vegas (est. 1905) rests upon ancient sacred groundwater, adjacent to Nüva Kaiv (Mt. Charleston) and Red Rocks–places of creation and mythos. Since long before the first casinos were erected, Nüwü have stewarded one of the most beautiful places in all of the Mojave Desert. They are basket makers and desert peoples; they gather pine nuts, and they survive unimaginable changes to their homelands–I imagine one of the most drastic transformations in US history. Their modern-day reservation, known colloquially as “The Colony,” is near Fremont Street.

Fawn’s identity is contextualized in the carefully curated cultural accoutrement that surrounds her. We designed her dollbox with love for mid-century modern Las Vegas design. Blending time and symbology because they coexist in a compressed timeline of cultural collision. Nüwü and Las Vegas are both a part of the people–sometimes these stories of survival are ironic and quirky, and bring layers of complexity that are a truth. Spend time with the objects with contributions by Everett Pikyavitt, Uncle Lamar ‘Este” Anderson, Leah Mata Fragua, and Fawn herself.

Fawn is an artist, activist, community leader, and former burlesque dancer based in Las Vegas. She is the head matriarch of Nüwü Art Studios + Nüwü Art Gallery + Community Center, and is also a board member for the nonprofit IndigenousAF. This portrait from the series honors Fawn’s enduring leadership and her work at the confluence of art, identity, and Indigenous sovereignty–grounded in the power and presence of the Las Vegas Paiute Nation. We hope this photograph imparts a glimmer of knowledge that sparks an interest in learning and honoring the legacy of the Nüwü.

NICHOLAS GALANIN

I Think It Goes Like This, 2024

Nicholas Galanin’s installation begins with an Indonesian-made replica of a Northwest Coast totem pole, a tourist commodity stripped of ceremonial and cultural meaning. Painted bright yellow and chainsawed into pieces, the pole is reduced to firewood, symbolizing the emptiness of commercialized Indigenous objects. The fragments are then reassembled into a precarious, Jenga-like form, conceptually “re-indigenizing” the work through transformation.

Titled I Think It Goes Like This, the name is a wry, humorous nod to the confusion and absurdity – the “joke” – surrounding cultural misunderstanding. Galanin’s piece confronts cultural appropriation, questions authenticity, and reclaims Indigenous authority to define its own meaning and integrity.

American Talking Stick, monochrome, 2023

.Nicholas Galanin’s Talking Stick transforms a traditional Indigenous symbol of dialogue into a white porcelain police baton, gilded with the Great Seal of the United States. Porcelain – a material rooted in European colonial trade – embodies the fragility of the power structures it critiques. Suspended gold finials bearing a metal eagle and a bullet casing create a precarious balance, symbolizing how violence and nationalism underpin American authority. Galanin exposes the contradictions of patriotic imagery, reclaiming Indigenous ceremony to confront systemic oppression and outdated histories.

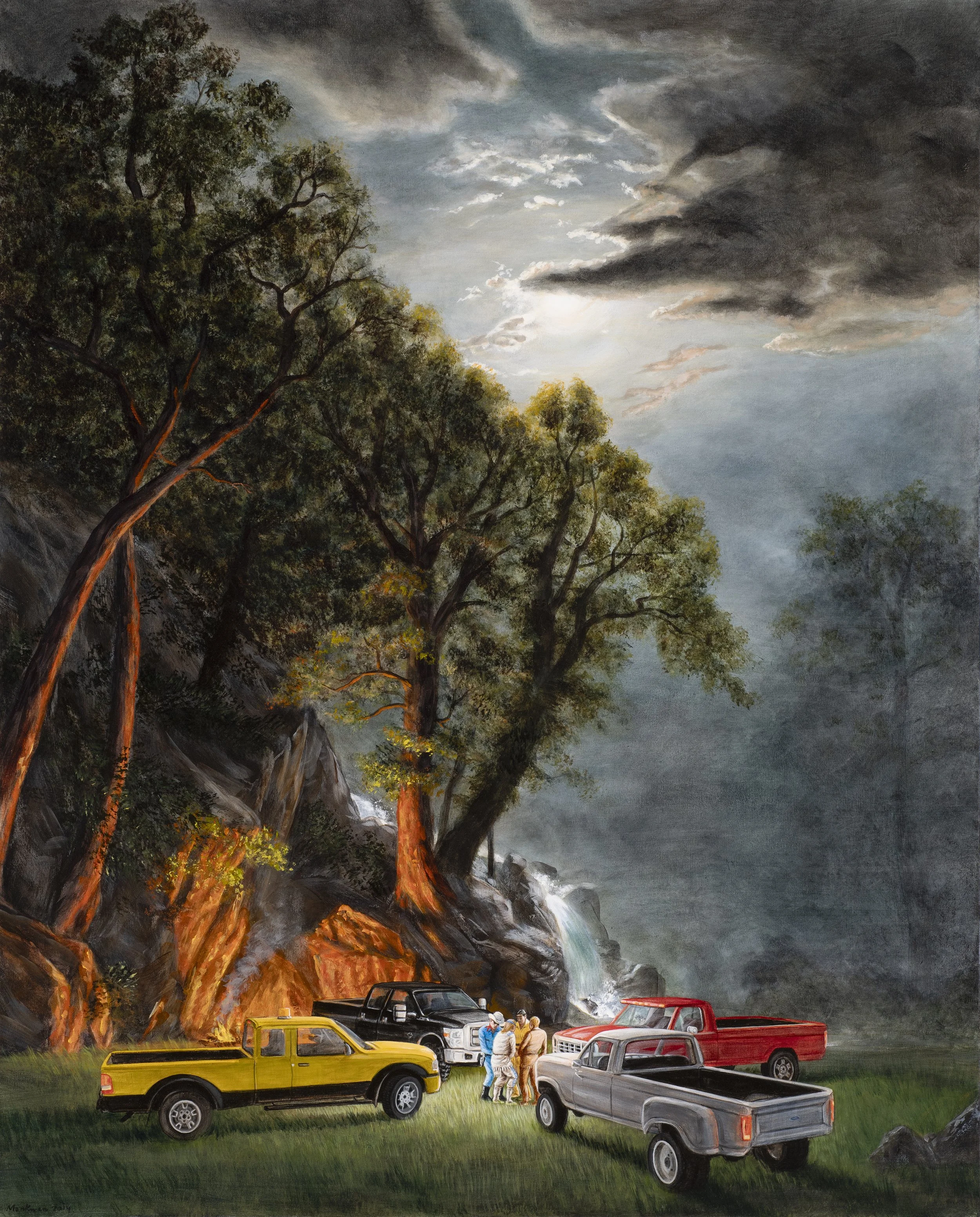

KENT MONKMAN

The Annunciation, 2025

Set against a Bierstadt-inspired mountain landscape, The Annunciation depicts Indigenous and Anglo men wrestling, playing music, and celebrating by the lake, all charged with Monkman’s sharp satire and humor. Floating above them is Monkman’s alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle – a Christ-like figure who both blesses and playfully challenges narratives of power and identity. A bare-chested, painted Scotsman draped below the waist humorously blurs cultural lines, recalling historic Rendezvous gatherings as sites of alliance and cultural negotiation. The painting reclaims a landscape often erased by Western expansion, repopulating it with Indigenous presence, queer resilience, and ironic wit.

The Ford Erections, 2014

In this rare nightscape, four Ford trucks illuminate a theatrical scene. At the center stand the Lone Ranger and Tonto alongside Winnetou and Shatterhand – fictitious figures rooted in settler fantasy and European myth-making. Positioned according to the four sacred directions with corresponding color symbolism, the trucks’ headlights spotlight the men as if on stage, emphasizing the performance and artifice of these colonial constructions. Through biting humor and irony, Monkman critiques the appropriation and commodification of Indigenous cultures and lands, inviting reflection on the manufactured myths imposed upon Native identity.

NICO WILLIAMS

NDN Market Essentials, 2025

Nico Williams’s NDN Market Essentials presents four distinct “sets” in vibrant orange, yellow, green and light blue – each comprised of a trucker hat, a lighter, and a pack of American Spirit cigarettes. At first glance, these everyday objects evoke consumer culture and modern convenience, yet Williams transforms them through meticulous beadwork – a deeply rooted Indigenous art form – into vibrant, handcrafted statements.

By recreating commercial commodities entirely with beads – including the cigarette packs, lighters, and hat emblems – Williams humorously and critically asserts Indigenous presence within mainstream culture. The work plays with themes of identity, appropriation, and resilience, using Indigenous-inspired humor to challenge the boundaries between tradition and contemporary life. NDN Market Essentials is a witty, vibrant celebration of the complexities of Indigenous existence today.

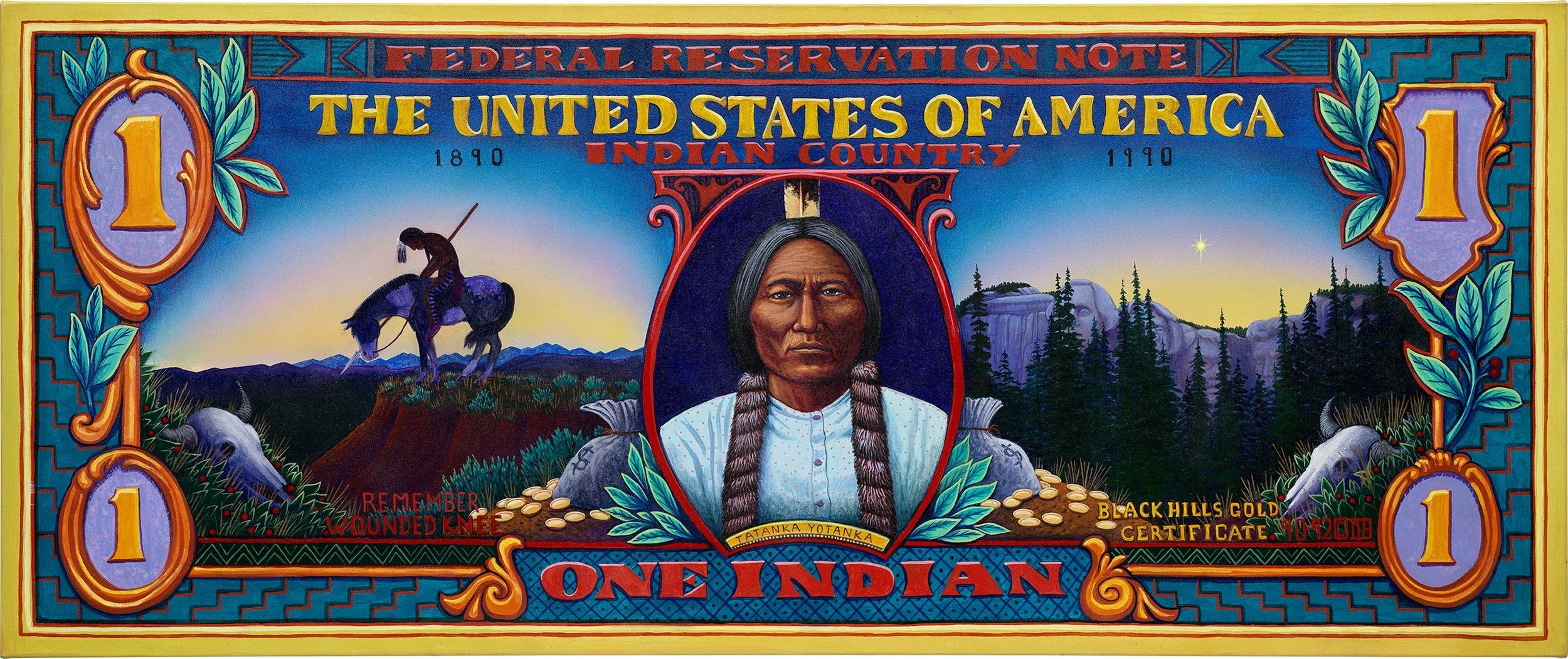

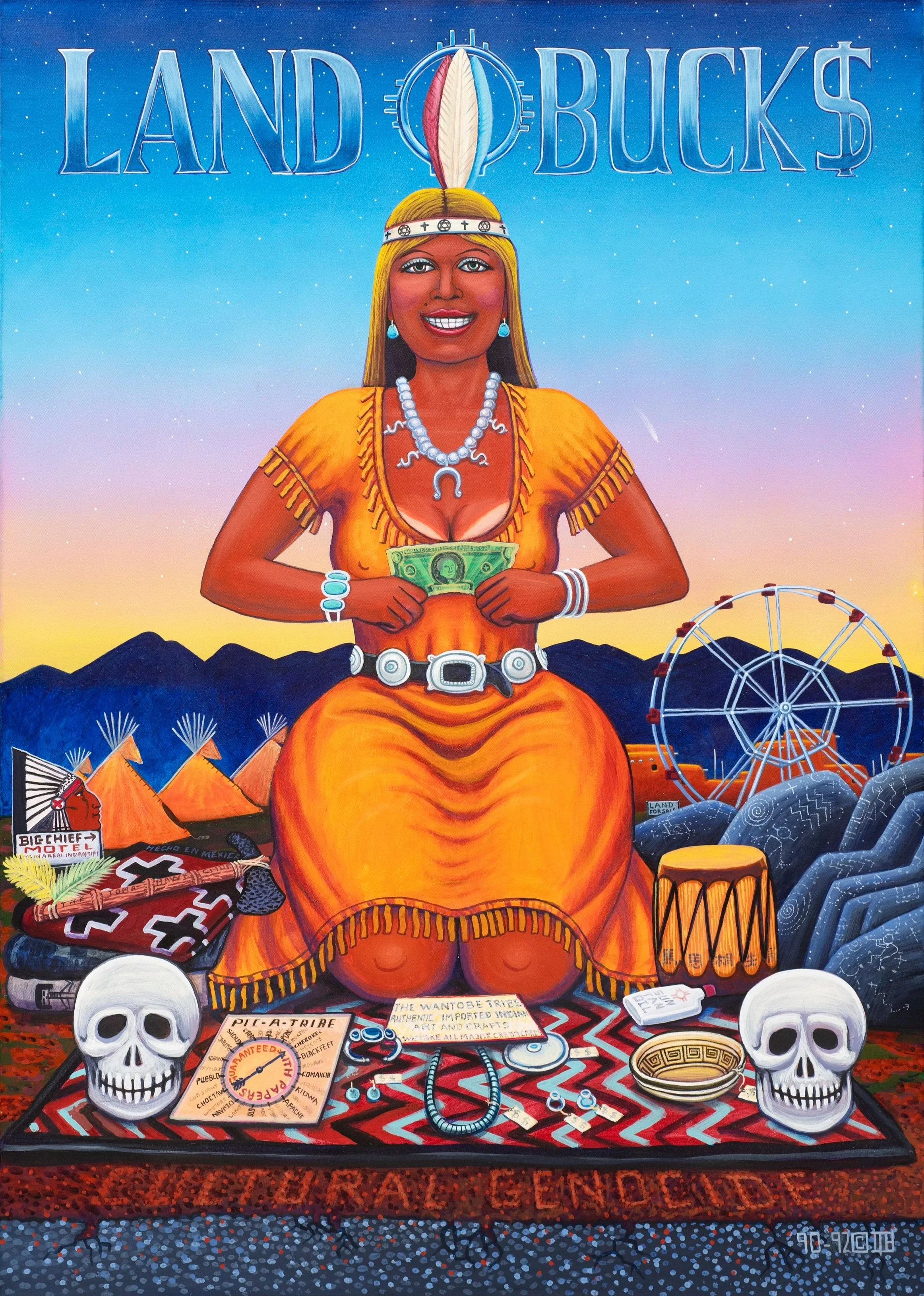

DAVID BRADLEY

Black Hills Gold Certificate, 1990-92

David Bradley’s Black Hills Gold Certificate reimagines a U.S. dollar bill as a vivid commentary on Native American history and the exploitation of the Black Hills. “One Dollar” becomes “One Indian,” George Washington is replaced by Sitting Bull, and bags of gold and animal skulls evoke the violent dispossession of Native lands. With its flat, vibrant surfaces and ironic “certificate” form, the work exposes the uneasy intersection of wealth, history, and the commodification of Indigenous identity.

Land O’Bucks Revisited, 1990-92

David Bradley’s satirical painting transforms the familiar Land O’Lakes butter image into a biting commentary on cultural appropriation. A kneeling woman appears to embody Native tradition, yet her blue eyes, dirty-blond hair, and painted-on tan expose her as an Anglo impersonating a romanticized, sexualized stereotype. Teepees, adobes, a Ferris wheel, and a “Big Chief” hotel form a backdrop of tourism and fantasy, while the blanket before her holds skulls, liquor bottles, and an “appropriation” board game. In her hands she offers a single dollar bill, and faintly inscribed beneath the blanket are the words “cultural genocide.” Bradley’s painting dismantles nostalgia to reveal the commodification and erasure beneath the American imagination.

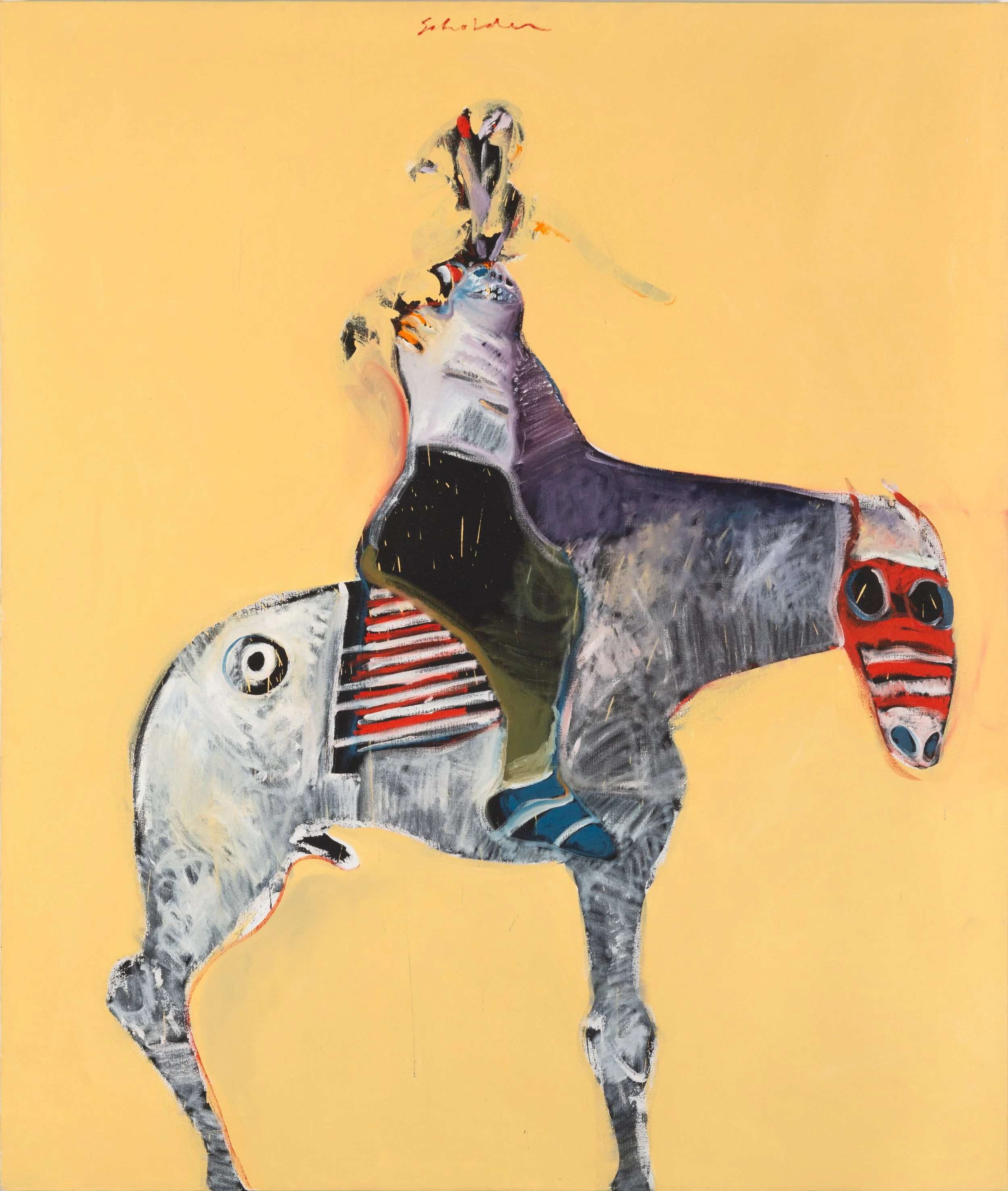

FRITZ SCHOLDER

Indian on Horse, 1970

Fritz Scholder’s Indian on Horse confronts the dramatized, romanticized image of the Native American embedded in American culture. A mounted warrior in full battle regalia remains upright, yet his head is violently struck away, while the horse’s glaring, ironic expression seems to challenge the viewer and beg’s the question of “well, what’s next?”. Referencing scenes made iconic through books, Wild West shows, and Hollywood films, Scholder transforms familiar imagery into a mirror of cultural misunderstanding and projection. Through bold color, distorted form, and emotional intensity, the work dismantles the mythic “Indian” and opens a space for dialogue on the anguish, resilience, and lived realities of Native experience.

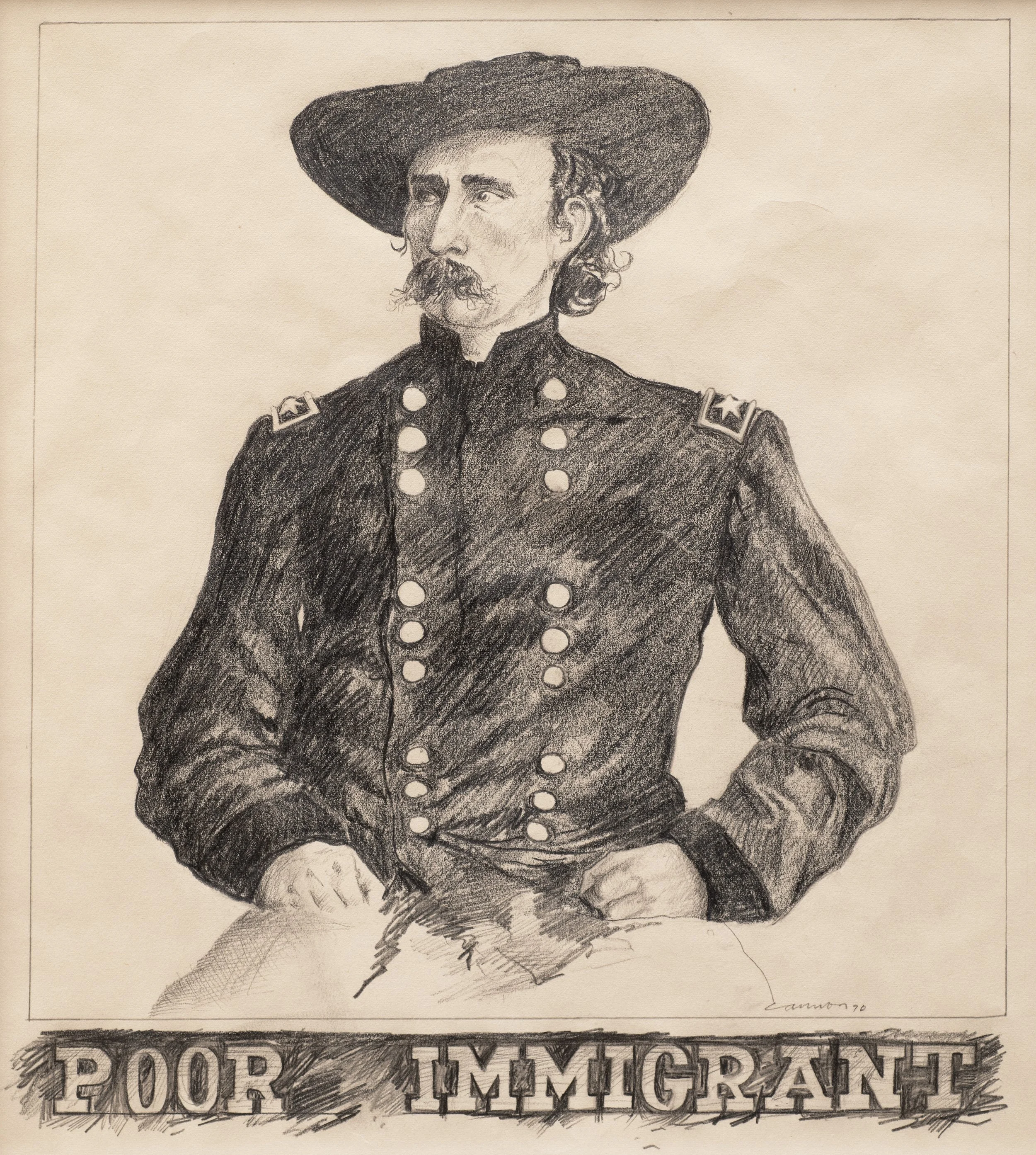

T.C. CANNON

Poor Immigrant, 1970

TC Cannon’s graphite drawing reimagines General Custer – a symbol of American expansionism – through a contemporary lens. Rendered with exquisite detail, Custer is shown in iconic military attire, overlaid with the pop art-style text “Poor Immigrant.” The phrase challenges heroic myths, recasting Custer as an outsider and exposing the violent colonial legacy. Combining precise draftsmanship and bold text, Cannon invites viewers to reconsider history and the narratives that shape identity and power.

BOB HAOZOUS

Bent Bonnet, 2000

Bob Haozous’ Bent Bonnet powerfully embodies the forced blindness imposed on Native peoples through colonial oppression. The figure’s eyes are fully covered by an elongated, textured bonnet – an arresting symbol of cultural erasure and silencing. Through its monumental form and striking contrast between smooth and patterned surfaces, the sculpture confronts the viewer with the ongoing struggle for Indigenous visibility, agency, and truth in the face of historical and systemic concealment.

Wire Face, 2004

Bob Haozous’ sculpture confronts the tension between Native identity and the machinery of modern life. A monumental figure in stone and steel, the man’s face is engulfed in barbed wire, transforming the headdress of honor into a shroud of erasure. The opposing side is sharply cut, embedded with a heavy steel ring that reduces the human form to an industrial object. Barbed wire was used to “tame” the West, part of the idea of Manifest Destiny. It was applied to separate open land into private property. Barbed wire is also a symbol of prison and concentration camps. The steel ring evokes the history of enslavement where rings like this were used to chain slaves.

This split, weighty form becomes a powerful metaphor for survival, cultural confinement, and the enduring impact of history. The work is a stark, unforgettable demand for recognition.

Coyote with Tongue, 1987

Bob Haozous’ steel coyote head combines rugged strength with playful energy. The compact, heavy form is enlivened by a long red tongue and flowing wavy weld lines, capturing the coyote’s restless spirit. This sculpture reveals the animal’s fierce yet lively character beneath its industrial exterior.

RICHARD GLAZER DANAY

Polarization, 1982

Glazer-Danay transforms a shoe shine box into a surreal commentary on climate change and cultural collision. Painted in arctic blues with flashes of red, purple, and green, its sides replace Darwin’s human evolution with a human-to-penguin shift and a penguin-to-buffalo transformation. Pop icons – a wind-up car, bold red lips, psychedelic patterns – collide with painted glaciers, contrasting distraction with crisis. Inside, a black-painted polar bear evokes wildlife consumed by oil, making Polarization both playful and urgent.

Wail, 1970

Wail presents a surreal tableau of creation and destruction aboard a massive toy whale. A blazing comet leads the way; nude Adam and Eve face a distant city on one side, while two dinosaurs inhabit the other. Atop, a hollow casket cradles a light-blue toy Indian chief, blending sky and resting place. The black base conceals a battlefield strewn with skeletons and rubble, symbolizing hidden devastation. Through myth and history, Wail mourns loss and invites reflection on environmental ruin and Indigenous histories.

A Home Where the Buffalo Can Roam, 1984

At the front, a gold-painted cowboy leans forward in charge, balancing a long blue-and-red polka dot projectile on his head. Each side panel shows a burning alien planet. On one side, a rabbit dressed as Alice in Wonderland shoots a cat; on the other, a baboon fires at a rhino. On the back, a pink buffalo emerges halfway from the box, stalked by a crouching toy “Indian” inside. Atop the work, a Nazi-like golden eagle towers over green pigs with gold dots as a kneeling woman offers praise. Raised near the spectacle of Coney Island, Glazer-Danay turns the title’s open-range promise into irony: here, the buffalo’s home is a satirical stage for conquest, greed, and the illusions of freedom.

JAQUE FRAGUA

Battle of Los Angeles, 2025

Battle of Los Angeles abstracts a charged scene of protest and power. Riot police, protesters, press, an American flag, and signs reading “stolen land” and “ICE” emerge from swirling colors and forms. Fragua’s painting captures the energy and complexity of social unrest, exploring themes of sovereignty, displacement, and resistance through layered, overlapping imagery.

June Tear Gas, 2025

Untitled, 2025

GEORGE ALEXANDER

John Wayne Dies This Time, 2025

With humor and flair, John Wayne Dies This Time overturns the old Western tales that cast Native Americans as villains. A boy wearing a slick Oklahoma western hat with bandana wields a supersoaker water gun topped with a buffalo, confronting the reflected image of John Wayne in his sunglasses, an icon of Hollywood stereotypes. Alexander’s vibrant painting reclaims Indigenous identity with playful defiance and colorful pride.

KATHLEEN WALL

White Bread Sandwich, 2025

Kathleen Wall’s installation addresses the history of Native child removal and cultural assimilation. A retro photograph shows a white couple joyfully doting on a small Native child in ironic costume regalia, seated at their table amid crustless sandwiches and a green Jell-O mold. In the gallery, the table, lamp, and food are physically recreated, blurring memory and reality. With humor and precision, Wall exposes the legacy of adoption and cultural erasure, revealing how domestic ideals once masked the systemic removal of Indigenous children from their families and communities.

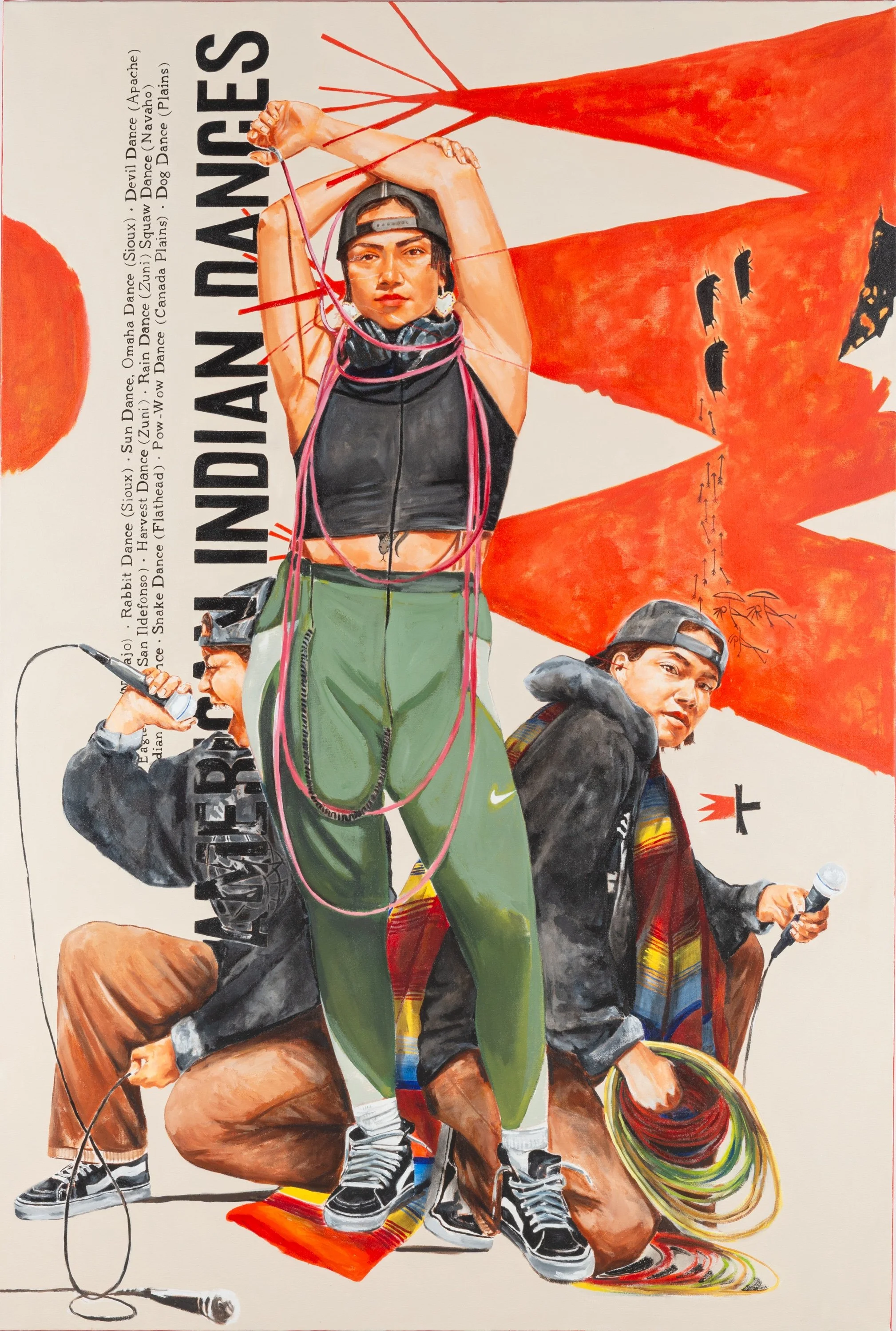

DC ALLEN (Baaa T’- chiilash)

Sovereign Sound, 2025

Sovereign Sound satirically confronts the colonial legacy of the Smithsonian vinyl American Indian Dances, which reduced living Indigenous music to commodified artifacts. Olivia Komahcheet – musician and activist – appears surrounded by microphones and cords, reclaiming space for vibrant, evolving Native sound. Ledger-style hunters, buffalo, and sunset-orange text evoking teepees frame a world where ceremonial dances were once flattened into tracklists.

Allen’s dynamic composition asserts that Indigenous music is not relic but sovereign – resilient, defiant, and uncontainable.

GLEN LA FONTAINE

Untitled, circa 1980s

Glen LaFontaine’s ceramics merge Native tradition with the playful irreverence of 1960s–70s Pop Art. Ceremonial chiefs and drummers bear anguished yet theatrical expressions, while ledger-style horses and thunderbirds mingle with shiny cars and green buffaloes stamped with whimsical dollar signs. This vibrant fusion offers a wry commentary on identity and stereotype, blending history with humor and resilience. LaFontaine’s work invites us to see Indigenous culture as both profound and playfully adaptive.

Winter Singer, 1985

Eagle Mask Man with Drum, 1983

ROXANNE SWENTZELL

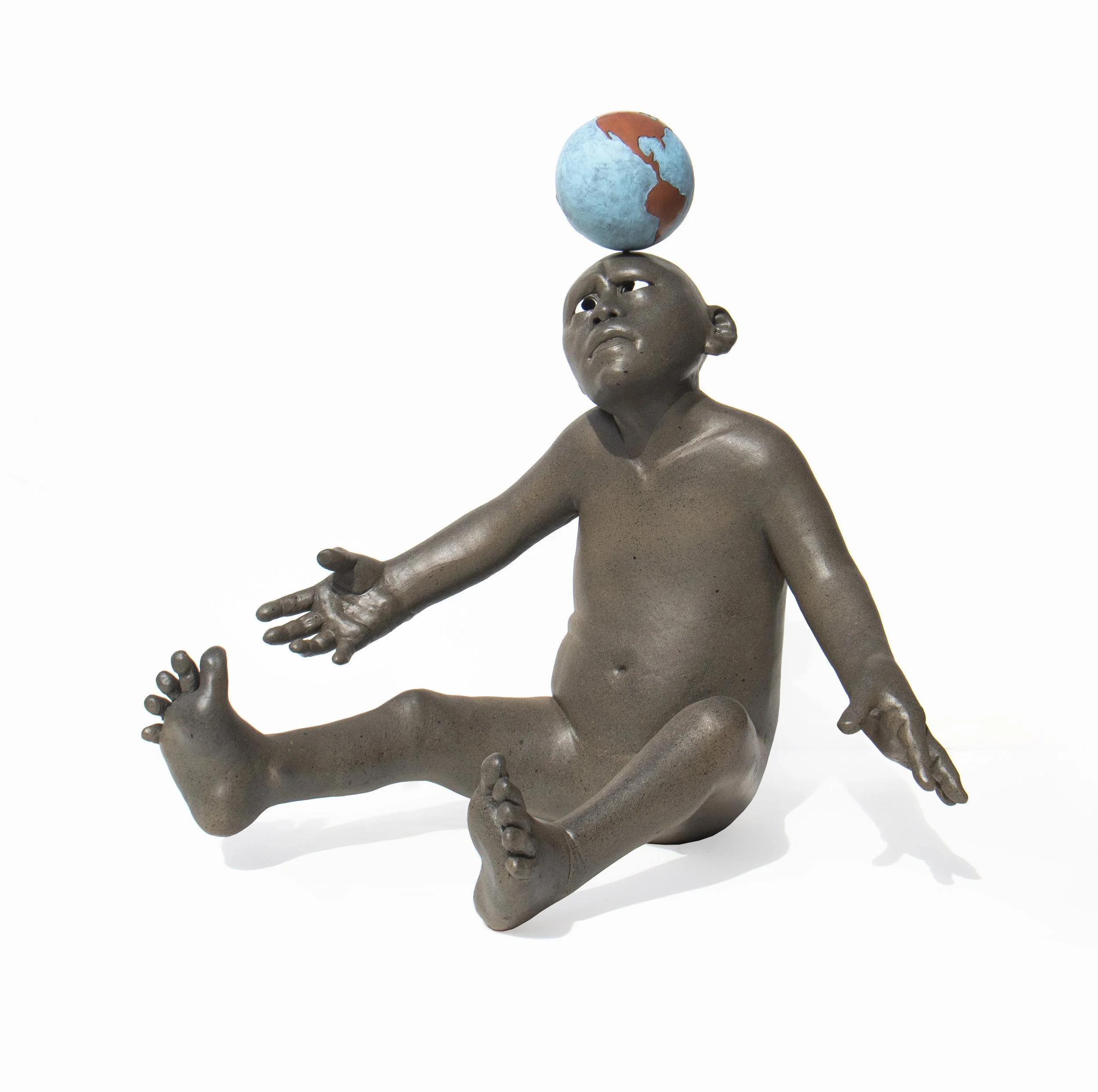

Unstable World, 2020

Roxanne Swentzell’s ceramic sculpture depicts a bald, possibly non-binary figure struggling to balance a brightly colored globe of the Earth atop the head. Flailing limbs and crossed eyes express the fragile tension of stewardship – a core Indigenous principle – amid the complex and urgent environmental challenges of today’s world. The muted, natural tones of the figure evoke a deep bond with the land, while the vibrant globe symbolizes the delicate balance between humanity and nature.

RICK BARTOW

Coyote/Madonna, 2015

Rick Bartow’s Coyote/Madonna fuses sacred archetypes and unsettling realities through bold expressionism. At its center, a pursed-lipped woman is confronted by the trickster Coyote, whose mischievous presence looms in the upper-right quadrant. From beyond the canvas, two disembodied hands grasp her breasts – an intrusion that evokes themes of violation and powerlessness. Bartow’s work refuses resolution, inviting the viewer to feel rather than explain, to confront discomfort, and to sense the raw power that lies in survival and storytelling.